It began with the rambunctious, big-hearted Disney adaptation of Jilly Cooper’s Rivals. What an opening, as the archetypal rake, Rupert Campbell-Black, and his companion, join the mile high club on Concorde while fellow passengers smoke, read Vogue magazine and pop champagne. Tres amusant!

As soon as it was over I ordered the books. Wintertime requires novels that are silly and fun with enough substance to really chew on, and big plots that hit the 700-page mark; something to keep you thoroughly distracted. It’s a struggle to find anything that fits the bill, but Jilly Cooper is the jackpot. I began with Riders, the first instalment in the Rutshire Chronicles. The cover art was, of course, a jodhpur-clad bottom (my four year old son no doubt assumed I was reading a book about farts). I know nothing about show jumping, and I have never, in my life, felt an urge to read about the sex lives of the landed gentry, and yet, and yet… Jilly knows what she’s doing.

Riders is set in the 1970s, while Rivals inhabits the more explicitly striving, materialistic 1980s. Let’s get this out of the way: there are many sex scenes, which range from ecstatic to slightly deranged to very camp. The books are also really funny. One character, searching her bed for any stray hairs left by her lover, Kevin, before her husband gets home, jokes with herself that she’s looking for Kevidence. These are deeply unserious people. In Riders, characters quote and misquote famous literature, and in Rivals this comes to the fore with a littering of references to A Midsummer Night’s Dream (the plot, stuffed with intrigue, disguises and mismatched pairings, takes much from the play). The world is tight-knit – a map in Rivals shows the few miles of the affluent Cotswolds covered – and the English countryside is exquisite and uplifting in every season. Cooper hits a bullseye every time with her depictions of social norms and habits. Everyone is a snob, but nobody’s prejudices are quite alike. Young husband Rupert, with his first wife, considers her suggestion that he be present at the birth of their child ‘too Islington for words’. Politics is local, limited to an ongoing seesaw between the Tories and ‘the socialists’. The rest of the world is a handful of holiday destinations: America is where you go to buy a horse, France and Spain are where you ‘hop’ for a long weekend. The American president makes a cameo in Riders but he is not permitted a name.

The behaviour of the men in Riders is often misogynist and brutal; rape is hideously downplayed (fun gets out of hand!) throughout, and though the men make elaborate threats of violence towards each other, only the women suffer real injury. The men are noticeably softened and given more emotional notes to play by 1987. Rupert is fairly menacing and often violent in the 70s; by the 80s he’s a touch calmer, works harder, and yes, it’s time to acknowledge his inner sadness. In Rivals, women can be aggressive and demanding, a new departure, and this is tolerated by the men and occasionally celebrated. Even the mousy wives get a mote more respect than their 70s sisters (one of the men despairs of having to sit next to the ‘unachieving wives,’ at dinner, but he’s the villain, and his mercenary, ungenerous attitude is the target.) Then there’s money. There’s never enough of it, and for all the trappings of aristocratic life (the casual mention of selling a Gainsborough if you have a cash-flow problem), there’s a sense that everyone’s putting on a front. The roofs of these stately homes are in constant need of repair; five-figure overdrafts hang heavy on the mind. Details like this abound, and give the comedic plotting a steel backbone. If this series had been written by a man, it would have been published in the 1980s to much fanfare as social satire, rather than bonkbusters. But who’s to say which marketing choice would have made the most money (as Rupert and his cohort would no doubt think to question)?

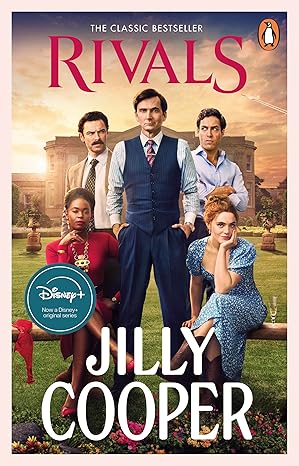

My edition of Rivals was a re-issue to coincide with the Disney series, and the blurb on the back seems to be endeavouring to prepare the reader for a whole lot of very un-woke behaviour: the 1980s is ‘a time when the affluent elite exist in a bubble’ and Rupert is ‘everyone’s favourite hate-to-love-him bad-boy.’ I often read 1970s Mills & Boon for the retro glamour of it all (‘setting’ a hair-do; typewriters and cigarettes and ‘I’ll check my diary’), and a certain amount of leeway is required. Like suspending disbelief for a fairy-tale, you have to suspend disapproval if you want to enjoy the style, the vintage fashions, the promise of a happy ending, the low stakes, gentle rise and fall of peril and mayhem. If you let go of the impulse to have a moral reaction, you can just stay fascinated. Did people really behave like that? Did a knitted jumper with a motif of Donald Duck really seem like appropriate office attire?* Sit back, relax, and enjoy the flight.

Unlike Mills & Boon romances, in which the point of view never strays from the virtuous heroine, the Rutshire Chronicles are written in limited third person, so we get to tag along with both sides of a rivalry or entanglement. We’re often inside the mind of Rupert, the promiscuous, dissolute cad. What struck me when I was reading these books is how often they explore what it feels like to be the hero, the object of female desire. Cooper is offering her readers (mostly women) a buffet of ways of wanting and being wanted, and it gives the books a wonderous sense of freedom and lightness. Comedy is just the vehicle for subversive play: we can do what we want, because we’re just joking, and anyway, all’s well that ends well. I wondered how many women had read these books for the thrill of being Rupert for a while. Desire in Cooper’s books is roaming and absolutely indiscriminate: bodies are always interesting, and variety is the seasoning of everyday life. Nobody in the book has a ‘type’; everyone finds something attractive about everyone else.

That’s the fantasy, and it is (as they might have said in the 80s) a whopper. Nowadays, with the internet and all, there’s so much hatred sloshing around that its easy to forget there are positive aspects to our base selves. Perhaps the most retro part of these books is the characters’ unwavering interest in having a good time, the blistering dominance of ego. It was immensely soothing to tarry a while with these ravenous people, egging them on as they make terrible decisions with minimal consequences. It’s not like they’ll get cancelled. If almost everyone in Rutshire suffers from a complete absence of control over their desires and appetites, the most frequent obsession is food. Characters in disarray are always discovered and carried off to a nearby restaurant for (as a minimum) champagne and steak. People are always rescuing one another, and it’s just wonderful. Low moods are summarily dismissed as a symptom of tiredness and hunger, and the answer is always a big meal and a good sleep. Perhaps this is more often true than we’d like to think. Drinks are described in great detail: jugs of Pimms in the garden, with oranges, strawberries, cucumber and mint; Dom Perignon over a quick catch up; margaritas (salt water with added salt water, Rupert calls them); a double whisky gulped down in moments of crisis. It was funny to compare this with the food in the Cazalet Chronicles (another series of books about English families, with a big cast, big houses, and beautiful countryside). The poor Cazalets, in the 1930s and 40s, eat terrible food, soggy cabbage with mystery meat that is almost always rabbit. The coffee is memorably described as ‘grey’. By the time the glitzy 80s roll around, you can grab saffron at the shops. You can even have an avocado, if you fancy.

Reading about the outsized exploits of a group of incorrigible rogues has been medicinal and necessary this winter. I tend to walk on the shaded side of the street, obsessively checking the news and getting mired in despair (or realism, as despairing folk might call it), about the state of the world. The Rutshire Chronicles isn’t here to right historical wrongs or elucidate a way out of hell for humanity, but it does something else, something vital: it makes you happy. For a while. Which is what we need, if we’re going to carry on. These books reminded me that life can occasionally be, you know… fun.

While I wouldn’t recommend the rampant alcohol consumption or the affairs, I do intent to start afresh in 2025 by venturing over to the sunny side of the street now and then. There are nine more books in the series, so I don’t have to give up this love any time soon. I’m planning to wear more adventurous jumpers, fluff up my hair, and always remember that a big meal and a good sleep solve many ills.

*The lovely Daysee at Corinium Television wears a series of knitted jumpers with cartoon characters on them, with an eye to impressing her colleagues with her fashion choices.

Leave a reply